The jungles in Guatemala’s northern reaches are some of the most biodiverse forests north of the Amazon. They’re one of the last remaining homes for jaguars, tapirs, and scarlet macaws. And they’re being systematically destroyed.

There are a number of factors that contribute to deforestation in Guatemala, but the impact of drug trafficking has had a measurable effect. Drug traffickers set up shop in the region, grabbing up land and tearing down trees to build landing strips for airplanes, or to set up farms, which they use to launder money. Narco-deforestation, as it’s known, has long been a problem, but America;s opiod epidemic is almost certainly making it worse.

It’s a link that hasn’t yet been made by researchers, but data from conservation, drug policy, and health literature add up to a compelling indication that our addiction to painkillers is playing a role in the destruction of this precious ecosystem.

Widespread addiction to opioid painkillers like OxyContin has expanded the US market for heroin, which is almost identical chemically to prescription opioids. Heroin is also usually cheaper than pills. It can be more readily available, and is more potent. With more demand for heroin in the US, drug cartels in Central and South America have even more incentive to continue tearing down the rainforests, and statistics show that deforestation has continued to climb right along pace with our growing appetite for heroin.

I first learned about this connection during a reporting trip to central Guatemala. Fascinated by the networks at play influencing the opioid epidemic in the US, I was curious if it had had any impact in Central America. So one afternoon, while driving to visit some indigenous midwives in the hilly, bucolic Tecpán region, I turned to my interpreter to ask if she knew whether the drug trade had changed at all in recent years.

She nodded emphatically, telling me it’s “gotten worse,” and that drug cartels in the north of the country were “chopping down the rainforest.”

“Is it just cocaine?” I asked her.

“Cocaine,” she acknowledged. “But heroin, too.”

Guatemala’s rainforests are one of the most diverse ecosystems on the planet. Image: Walter Rodriguez/Flickr

Between 1990 and 2005, 17 percent of Guatemala’s total forest cover was torn down—a loss of roughly half a million hectares of trees—according to the European Agency, which tracks deforestation using satellite imagery. It’s continued at a similar pace since then, particularly in the ecologically vulnerable rainforest areas, where an increase in drug trafficking coincided with as much as 10 percent forest loss between 2006 and 2010.

And it’s only getting worse.

“It hasn’t slowed down in the last four years,” said Matthew Taylor, a professor of geography and the environment at the University of Denver, who has studied the impacts of drug trafficking on the environment. “From speaking with my sources and from evidence from being in the field, it’s increasing.”

Though agriculture and logging account for a large portion of this deforestation in Central and South America, the narco-deforestation has played a significant role, too. The actual cultivation of drugs like cocaine and heroin has an impact: The Organization of American States estimates that 2.5 million hectares of Amazonian forest in Peru have been destroyed to grow coca, while more than 1 million hectares of forest in Colombia have been culled to grow illicit drugs, including opium poppies for heroin.

But in Central America, the drug-related deforestation is caused instead by all of the activities surrounding the trafficking side of the supply chain, according to Kendra McSweeney, the study author and a professor of geography at Ohio State University.

“[Traffickers] need a lot of land through which to move drugs,” McSweeney told me. “In order to secure those routes, they like to buy up the land and cut forests for landing planes, landing boats, unloading, reloading, and driving out by car.”

Drug cartels also buy land and cut down forests to establish cattle ranches, which make handy businesses through which to launder money, McSweeney explained. It also gives them a diversification option: If the drug route gets cracked down, they still own the land, which they can sell off for major profits, since the original sale is usually made under duress (you can’t really negotiate real estate prices with a drug cartel).

“These are totally dynamics made in the USA, no question.”

These methods are causing increased deforestation, particularly in some of the most vulnerable ecological regions, McSweeney said. She and other researchers estimate that the drug trade is responsible for at least 30 percent of all deforestation in Central America, but as much as 50 percent in some regions—including Guatemala’s northern rainforests, located in the Petén department.

These drug trafficking organizations aren’t dealing strictly in heroin. Cocaine is the biggest product by far, and they also dabble in marijuana farming and even cooking methamphetamine. But in recent years, heroin has become a growing export from Central America, according to the Drug Enforcement Agency, which reported that heroin seizures at the US-Mexico border more than doubled between 2010 and 2015.

Much of the heroin is coming directly from Mexico, but the DEA also reports that heroin coming into the US is produced in Guatemala and Colombia, and trafficked through networks across Central America. It’s difficult to pin down exactly how much of these cartels’ business is heroin, but it’s clearly playing a role.

“What is and is not run by those groups is obviously not something that’s public information,” said Ben Hodgdon, the global director of forestry at the Rainforest Alliance, an NGO that works to preserve forest biodiversity. “But these are criminal organizations that are tied up with trafficking any number of different narcotics, so I think it’s reasonable to highlight some kind of link.”

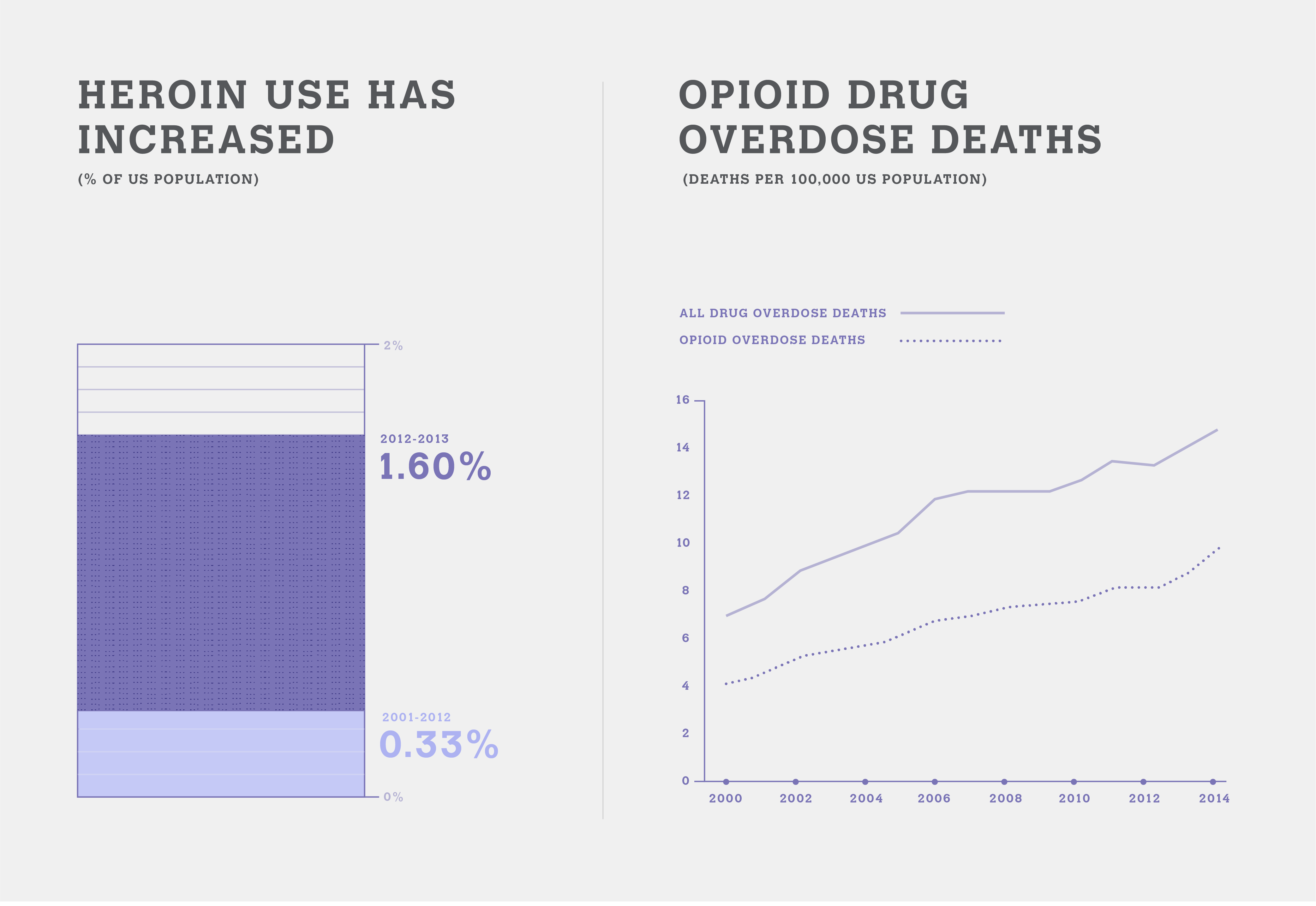

At the same time this drug trafficking-related deforestation was ramping up in Central America, the market for heroin in the United States was exploding. Between 2001 and 2013, the use of heroin in the United States increased five-fold, according to our sources. That means that by 2013, approximately 3.8 million US adults had used heroin at some point in their lifetime.

Data from CDC and Martins et al, JAMA Psychiatry, March, 2017 Image: Sarah MacReading/Motherboard

The Centers for Disease Control says that herion use in the US has increased across practically all demographics. It has more than doubled in young adults ages 18-25, and heroin overdose deaths are also on the rise. By 2013, the rate of heroin-related overdose deaths had nearly quadrupled the rate from 2002, with more than 8,200 people overdosing in 2013. In 2015, opiod overdoses surpassed homicide deaths in America for the first time in history.

Not all painkiller addicts go on to use heroin, but studies show a significant amount of new heroin users have previously abused prescription opioids. Between 75 and 80 percent of new heroin users have previously abused painkillers, and individuals addicted to prescription opioids are 40 times more likley to become addicted to heroin. We call it the opioid epidemic, instead of the OxyContin epidemic, because this scourge goes beyond prescription pills.

All of these factors add up to a disturbing conclusion: Our widespread abuse of prescription painkillers has led thousands of Americans who never would have used heroin to become addicted to the narcotic. This has driven up the demand for heroin, giving drug traffickers across Central and South America a bigger market to fill, and more means to continue their systematic destruction of some of the most unique and valuable ecosystems on the planet.

“These are totally dynamics made in the USA, no question,” McSweeney told me.

The experts I spoke to all said there are ways we can curb this destruction. McSweeney believes that steering drug policy in the US away from prohibition toward recovery and abuse reduction would ease a lot of the impacts on biodiversity conservation. Hodgson advocated for working to help local communities reclaim land rights in ancestral lands—his research shows drug cartels tend to steer clear of forest that’s already occupied.

And it’s clear that addressing America’s opioid epidemic, a goal President Donald Trump long promised but yet to meaningfully address, could have a positive influence. It won’t cure deforestation, or even narco-deforestation, completely. But it would help reduce the impact our addiction is having on some of the last remaining rainforest in this hemisphere.